We invite you to celebrate Ven. Pema's 80th birthday with an article that first appeared in Shambhala Sun (Sept '98), republished here with the gracious permission of Lion's Roar.

|

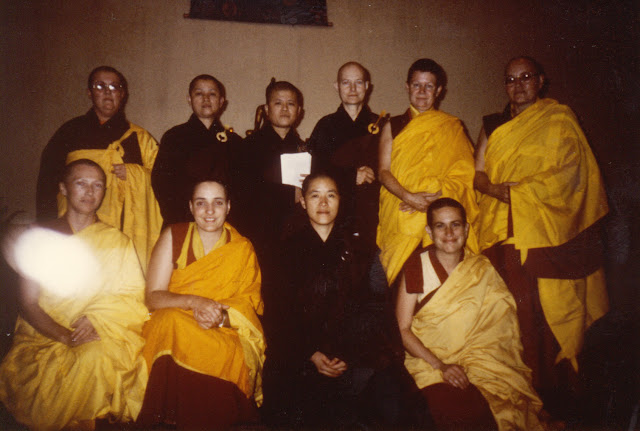

| Ven. Pema Chodron, a co-founder of Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women, at the 1st Sakyadhita International Conference held on Bodhgaya, India in 1987. Pictured top row, 2nd from right. |

To Know Yourself is to Forget Yourself

The journey of awakening happens just at the place where we can’t get comfortable. Opening to discomfort is the basis of transmuting our so-called “negative” feelings. We somehow want to get rid of our uncomfortable feelings either by justifying them or by squelching them, but it turns out that this is like throwing the baby out with the bath water. According to the teachings of vajrayana, or tantric, Buddhism, our wisdom and our confusion are so interwoven that it doesn’t work to just throw things out.

By trying to get rid of “negativity,” by trying to eradicate it, by putting it into a column labelled “bad,” we are throwing away our wisdom as well, because everything in us is creative energy—particularly our strong emotions. They are filled with life-force.

There is nothing wrong with negativity per se; the problem is that we never see it, we never honor it, we never look into its heart. We don’t taste our negativity, smell it, get to know it. Instead, we are always trying to get rid of it by punching someone in the face, by slandering someone, by punishing ourselves, or by repressing our feelings. In between repression and acting out, however, there is something wise and profound and timeless.

If we just try to get rid of negative feelings, we don’t realize that those feelings are our wisdom. The transmutation comes from the willingness to hold our seat with the feeling, to let the words go, to let the justification go. We don’t have to have resolution. We can live with a dissonant note; we don’t have to play the next key to end the tune.

Curiously enough, this journey of transmutation is one of tremendous joy. We usually seek joy in the wrong places, by trying to avoid feeling whole parts of the human condition. We seek happiness by believing that whole parts of what it is to be human are unacceptable. We feel that something has to change in ourselves. However, unconditional joy comes about through some kind of intelligence in which we allow ourselves to see clearly what we do with great honesty, combined with a tremendous kindness and gentleness. This combination of honesty, or clear-seeing, and kindness is the essence of maitri—unconditional friendship with ourselves.

This is a process of continually stepping into unknown territory. You become willing to step into the unknown territory of your own being. Then you realize that this particular adventure is not only taking you into your own being, it’s also taking you out into the whole universe. You can only go into the unknown when you have made friends with yourself. You can only step into those areas “out there” by beginning to explore and have curiosity about this unknown “in here,” in yourself.

Dogen Zen-ji said, “To know yourself is to forget yourself.” We might

think that knowing ourselves is a very ego-centered thing, but by

beginning to look so clearly and so honestly at ourselves—at our

emotions, at our thoughts, at who we really are—we begin to dissolve the

walls that separate us from others. Somehow all of these walls, these

ways of feeling separate from everything else and everyone else, are

made up of opinions. They are made up of dogma; they are made of

prejudice. These walls come from our fear of knowing parts of ourselves.

Dogen Zen-ji said, “To know yourself is to forget yourself.” We might

think that knowing ourselves is a very ego-centered thing, but by

beginning to look so clearly and so honestly at ourselves—at our

emotions, at our thoughts, at who we really are—we begin to dissolve the

walls that separate us from others. Somehow all of these walls, these

ways of feeling separate from everything else and everyone else, are

made up of opinions. They are made up of dogma; they are made of

prejudice. These walls come from our fear of knowing parts of ourselves.There is a Tibetan teaching that is often translated as, “Self-cherishing is the root of all suffering.” It can be hard for a Western person to hear the term “self-cherishing” without misunderstanding what is being said. I would guess that 85% of us Westerners would interpret it as telling us that we shouldn’t care for ourselves—that there is something anti-wakeful about respecting ourselves. But that isn’t what it really means. What it is talking about is fixating. “Self-cherishing” refers to how we try to protect ourselves by fixating; how we put up walls so that we won’t have to feel discomfort or lack of resolution. That notion of self-cherishing refers to the erroneous belief that there could be only comfort and no discomfort, or the belief that there could be only happiness and no sadness, or the belief that there could be just good and no bad.

But what the Buddhist teachings point out is that we could take a much bigger perspective, one that is beyond good and evil. Classifications of good and bad come from lack of maitri. We say that something is good if it makes us feel secure and it’s bad if it makes us feel insecure. That way we get into hating people who make us feel insecure and hating all kinds of religions or nationalities that make us feel insecure. And we like those who give us ground under our feet.

When we are so involved with trying to protect ourselves, we are unable to see the pain in another person’s face. “Self-cherishing” is ego fixating and grasping: it ties our hearts, our shoulders, our head, our stomach, into knots. We can’t open. Everything is in a knot. When we begin to open we can see others and we can be there for them. But to the degree that we haven’t worked with our own fear, we are going to shut down when others trigger our fear.

So to know yourself is to forget yourself. This is to say that when we make friends with ourselves we no longer have to be so self-involved. It’s a curious twist: making friends with ourselves is a way of not being so self-involved anymore. Then Dogen Zen-ji goes on to say, “To forget yourself is to become enlightened by all things.” When we are not so self-involved, we begin to realize that the world is speaking to us all of the time. Every plant, every tree, every animal, every person, every car, every airplane is speaking to us, teaching us, awakening us. It’s a wonderful world, but we often miss it. It’s as if we see the previews of coming attractions and never get to the main feature.

When we feel resentful or judgmental, it hurts us and it hurts others. But if we look into it we might see that behind the resentment there is fear and behind the fear there is a tremendous softness. There is a very big heart and a huge mind—a very awake, basic state of being. To experience this we begin to make a journey, the journey of unconditional friendliness toward the self that we already are.

Reproduced with permission of LionsRoar.com.

Venerable Pema Chodron Bhikshuni

|

| Ven. Pema Chodron at the 1st Sakyadhita International Conference held on Bodhgaya, India in 1987. Pictured 2nd from left. |

No comments:

Post a Comment